hree

outstanding artists of Black Boston in the last

century are Lois Mailou Jones (1905-1998),

Allan Crite (1910-) and Meta Vaux Warwick

Fuller (1877-1968). hree

outstanding artists of Black Boston in the last

century are Lois Mailou Jones (1905-1998),

Allan Crite (1910-) and Meta Vaux Warwick

Fuller (1877-1968).

All had distinguished careers and major exhibitions.

Crite and Fuller, working with Maud Cuney Hare's

Allied Art Players, also played a role in the development

of Boston's nascent black theater.

Lois Mailou Jones (1905-1998)

was born in Boston and lived with her parents and

brother on School Street, near the Boston Common.

She trained as an artist at the Museum School of

the Museum of Fine Arts.

A life-changing encounter occurred when she returned

from a trip to Paris: she met Alain Locke on the

campus of Howard University. As leader of the New

Negro Renaissance, Locke told her: "'. . .I wish

you would do more with the black subject, Lois Jones.

All of you artists have got to do something about

this movement. You've got to contribute as artists.'"

Jones stated for the record:

"So I took very seriously

what he said, to the extent that I immediately

went back to my studio apartment in Washington

and decided to do a subject which would deal

with lynching because we were having lynchings

ast that time in the '40s"(Oral History, Schlesinger

Library, 16).

That painting was "Mob Victim."

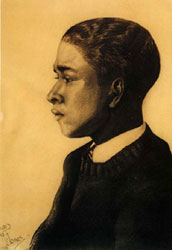

Jones then took up black themes in earnest: examples

are "Negro Youth" (see image below), 1929,

"Ascent of Ethiopia" 1932, and Cubist forms,

"Les Fètiches" 1938.

A s

a child Jones spent summers on Martha's Vineyard

Island, where her family and writer Dorothy West

rented summer houses next to each other in Oak Bluffs. s

a child Jones spent summers on Martha's Vineyard

Island, where her family and writer Dorothy West

rented summer houses next to each other in Oak Bluffs.

Jones' parents later bought a [Methodist] Campground

house and had it "rolled up" School Street to 21

Pacific Avenue, where it still stands. (Martha's

Vineyard Times, June 18, 1998, 2).

Also on the Vineyard, her mother

worked as a maid and ran her own hairdressing business.

Jones began studying art at an early age, encouraged

by her parents.

After Jones finished at the Museum School, fellow

artist Meta Vaux Warwick Fuller advised her

that she should go to Europe, where her race would

not be a barrier to success in art (Oral History).

Jones won a fellowship to the AcadÈmie Julian in

Paris in 1937. She was elated to discover that in

Paris a black woman encountered less prejudice than

at home.

Jones painted impressionistic

landscapes, Cubist- influenced abstractions and

subjects from recent black American history.

In 1930 Jones joined the faculty at Howard University

in Washington DC, retiring forty-seven years later.

Jones was not exempt from racial

incidents, however. In one particular instance,

her well known "Indian Shops, Gay Head, Massachusetts"

won the Robert Woods Bliss Prize for landscape in

1941 at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C.

But she had to have a friend submit the painting

for her and had to receive the prize by mail, because

the Corcoran at that time did not accept submission

from African American artists.

The Corcoran did, however, celebrate her work in

the last decade of her life (Martha's Vineyard Times,

loc. Cit.).

Jones, an important artist linked

to the trans-Atlantic idea of NÈgritute (CÈsaire

and Senghor), also won the distinction of being

the last surviving artist of the New Negro or

Harlem Renaissance.

For all of her prizes, one

of Jones' proudest moments came early on, when she

had her first one-woman show in her native Boston,

at the respected Vose Galleries on Newbury Street.

The distinguished sculptor Meta

Vaux Warrick Fuller was born in Philadelphia,

and came to Boston after studying in Paris at the

AcadÈmie Colarossi and the Ecole des Beaux Arts.

Rodin proclaimed her "a born sculptor"; Saint-Gaudens

allowed her to work in his own studio.

As with Lois Mailou Jones,

a meeting with a famous African American intellectual

led her to a turning point in her artistic career.

W.E.B. Dubois advised Meta to introduce African

and African American themes into her art and to

use art as an expression of the African-American

experience.

Dubois later commissioned Fuller to do a piece to

mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation

Proclamation.

Fuller's most famous sculpture, "Ethiopia Awakening,"

became symbolic of the rise in Pan-Africanism both

in thepolitical and cultural world."

When Meta Warrick Fuller married

Dr. Solomon Fuller, a distinguished psychiatrist,

the couple settled outside of Boston, in then rural

Framingham, where they raised their sons.

Fuller collaborated with black creative artists

living in Boston proper. Her name appears on the

playbills of the Allied Arts Players, headed

by Maude Cuney-Hare.

Before coming to Boston, Meta

Warrick had already established her reputation.

At thirty years old, fresh from the studios of Paris,

she accepted a commission "to construct in a true

and artistic manner" tableaux "so arranged as to

show . . . the progress of the Negro in America

from the landing at Jamestown to the present time."

Links of Interest:

A

display of the tableaux and a portrait of the

artist from 1907

An

excellent bio-article on Fuller and the scope

of her artistic career

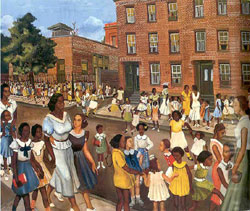

Allan Crite (1910) has

been a life-long Boston artist.

He was just ten months old when

his family moved to the city from Plainfield, New

Jersey. He has never lived anywhere else, though

Dilworth Street, where he lived as a child, was

erased by urban renewal (what Crite calls "urban

destruction").

His paintings, which depict

the Roxbury neighborhood of his youth, are now prized

as historical records for the city of Boston.

Crite's spiritual dimension is expressed in religious

scenes and altar pieces that can be found in chapels

and churches across the country.

Younger than Lois Mailou Jones by five years, Crite

followed her footsteps to the School of the Museum

of Fine Arts Boston (1939). He was one of the few

African American artists to work briefly for the

Federal Arts Project (FAP) in the 1930s.

Links of interest:

A

photograph of Allan Crite and an outline of his

artistic career

A

description of Crite taking a visitor through

his house museum

Beauford Delaney (1902-1979)

was born in Knoxville, Tennessee.

In

1923 he moved to Boston, where he took art classes

at the Massachusetts Normal Art School and the Copley

Art Society and met the poet Countee Cullen

and other intellectuals. In

1923 he moved to Boston, where he took art classes

at the Massachusetts Normal Art School and the Copley

Art Society and met the poet Countee Cullen

and other intellectuals.

This was a formative period of his life. In 1929

he moved to New York City and on to Paris in 1953.

His painting, figurative when abstract art carried

the day, did not at first get its due from art critics

and historians.

In Paris Delaney became fast friends with James

Baldwin, who in 1964 had this to say:

"[Delaney] has been starving

and working all of his life-in Tennessee, in

Boston, in New York, and now in Paris. . .More

than any man I know he has trasncended both the

inner and outer darkness."

Links of Interest:

The

career of Delaney, based on the biography

Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney (1998)

by David Adams Leeming.

Though lacking the access to patronage enjoyed by

many white artists of the times, Fuller, Jones,

and Crite were not the first of their race to find

inspiration in the city where Mrs. Isabella Stewart

Gardiner and the Museum of Fine Arts created an

art-loving climate.

Before Fuller, Jones and Crite

came sculptor Edmonia Lewis (1940s-c.1890).

Born in the middle of the 19th

century, part Chippewa Indian, part African-American,

and an orphan, Lewis was educated at Oberlin College.

As a child she roamed the woods with the Chippewas

and Chippewa heritage played a part in her work,

as did the black legacy. Her brother supported her

studies at Oberlin College in Ohio, a major abolitionist

center at the time. Later, in Boston, her desire

to become a sculptor took hold.

The neoclassical sculptor

Edward Brackett mentored her and she created

a medallion portraying the abolitionist leader John

Brown and in 1864 she completed a bust of Robert

Gould Shaw, the Civil War colonel who led an

African American regiment to glory.

From Boston this wanderer went

to Rome, home to many expatriate American artists,

including several women.

In her work she infused elements of her ethnicity

(including elements of Egypt, which she saw as African),

which was not always the case by any means for her

times.

She also used African-American themes in creating

works like "Forever Free," where she celebrates

the emancipation of slaves.

She was the first African-American, man or woman,

to pursue sculpture in great depth.

In Rome, Lewis was welcomed into a tight-knit circle

of American expatriates whose artistry was not confined

to sculpture or to painting, but encompassed acting

as well. Women could succeed in Europe, where they

could not in their own country.

For an African-American woman

Europe represented two-fold salvation. A discussion

of Lewis' career can be found at this

site.

Yet another African American

who made an early appearance on the Boston art scene

was Edward Mitchell Bannister (1828-1901),

born in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada, c. 1828.

Bannister

migrated to Boston, around 1848. Photographer, daguerrotypist,

1863-1865, and portrait painter, 1863-1872, he moved

to Providence, Rhode Island in 1869. Bannister

migrated to Boston, around 1848. Photographer, daguerrotypist,

1863-1865, and portrait painter, 1863-1872, he moved

to Providence, Rhode Island in 1869.

He received a Bronze Medal in

Art at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, 1876,

and founded the Providence Art Club in 1872.

Bannister served on the Board of Directors of the

Rhode Island School of Design (RISDI) in Providence.

|