by Brady Priest, Shayla Schneider, Marty Whited, and Brian Coates.

Archived from http://www.middlebury.edu/classes/fall97/ac400/group2/priest/brady.html

As the conflict in Vietnam escalated into something much more than the American people had originally expected, the media coverage of the War also expanded and played a dominating role in the shaping of public attitudes. The American people developed a voracious appetite for all Vietnam-related news events, and the journalists and news organizations obliged them by devoting more and more of their respective energies to the coverage of the War. As the 1960's came to a close, the stance of the American people evolved from one that was, for the most part, supportive of the war effort in Vietnam, to one that was decidedly against the Conflict. This transformation of public opinion was reflected on the front pages of major newspapers, the covers of leading magazines such as Time, and, in the studios of every television newsroom in the country. The anti-Vietnam protest movement was the news story of the late 1960's and early 1970's |

This media frenzy created an environment in which one image was able to shift the balance of public opinion one way or the other, for as long as it remained ingrained on the minds of the American people.

|

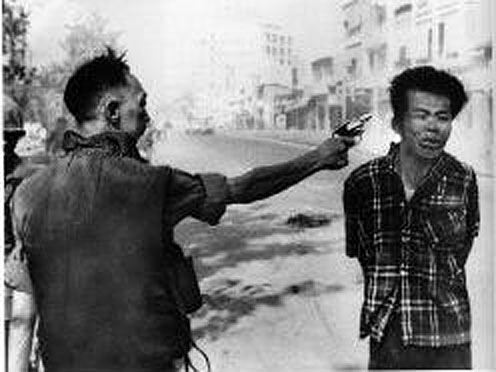

The renewed power of the single image naturally resulted in a conscious effort by journalists, and amateur photographers to capture sensational or otherwise noteworthy incidents on film. People like John Filo became celebrities overnight with pictures such as his of the Kent State incident. There are three such photographs from this era which stand out, both because of the shocking nature of their subject matter, and because of the enormous amount of public attention that they received- Eddie Adams' photograph of Vietnam's chief of police, Nguyen Ngoc Loan, shooting a suspected Viet Cong collaborator in the head, taken February 1, 1968; Filo's image of Mary Ann Vecchio kneeling over the dead body of Jeff Miller from May 4, 1970; and Huynh Cong "Nick" Ut's photo of the naked Kim Phuc and a group of Vietnamese children running from the cloud of deadly napalm behind them, captured on June 8, 1972. All three photographs won Pulitzer Prizes, and were seen by every American who was at all concerned with the War in Vietnam. |

The power of these three individual images is a testament to the prevailing attitude of the times, as people were searching for rallying points with which they could justify their anti-war sentiments in response to a government that wanted to write protesters off as unpatriotic or cowardly citizens. Pictures such as these three captured the ugliness and pain of a war that many Americans, by the end of the 1960's, no longer wanted any part of. This was a time like no other in American history, as so many Americans struggled to define their point of view with respect to the War- photographs like these three were used as propaganda to bring millions to the side of the protest movement.

By most accounts, the Tet Offensive of 1968 was the beginning of the end of America's positive outlook on Vietnam; not because American soldiers were defeated, rather, because of the way that Tet was portrayed by the press. In the words of Clarence Wyatt, author of Paper Soldiers, the press "turned a military triumph for the United States and the South Vietnamese into a "psychological victory" for the enemy" (Wyatt; p.167) . The Tet Offensive came at a time when President Johnson was attempting to reassure the American public as to the state of affairs in Vietnam (Braestrup; p.xxv), and was therefore a surprise to the majority of Americans. The American people were taken aback by the sheer number of deaths on both sides- 9,000 American and South Vietnamese soldiers, 14,300 South Vietnamese civilians, and 58,000 North Vietnamese troops (Wyatt; p.166)- but the most damaging piece of news to emerge from Tet was Eddie Adams' photograph.

Adams' picture of the imposing, militarily-clad General Loan shooting a young, smallish Vietnamese suspect in the head is undoubtedly one of the most disturbing photographs of the period. The suspected Viet Cong soldier is dressed in a plaid shirt, in contrast to General Loan, and has his arms tied behind his back. In effect, he gives the appearance of a defenseless young boy, and, although this description is probably far from the truth, the power of the photograph comes from the boys somewhat pitiful appearance, offset by the authoritarian stature of Loan. It is not surprising that this photograph dominated the American media for weeks, and even months after it was taken, as it became a symbol for everything that was going wrong in the Vietnam War. The photo personified for many the idea that the South Vietnamese, the very people that Americans were sacrificing their lives for, were not the helpless victims of a communist onslaught that the government would have had them believe, rather, they were a people just as capable as the North Vietnamese of all types of brutality.

Adams' photograph, which graced the front page of The New York Times the next day under the headline "Street Clashes Go On in Vietnam, Foe Still Holds Parts of Cities; Johnson Pledges "Never to Yield" (Braestrup; p.461) , served as fuel for the fire of the Vietnam protest movement. It probably inspired many editorials such as the one entitled "The Logic of the Battlefield" that was printed in TheWall Street Journal on February 23rd, 1968. In it, the editor states that "the American people should be getting ready to accept, if they haven't already, the prospect that the whole Vietnam effort may be doomed" . Opinions like this one spread like wild fire in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive. So, the American people, with the image of General Loan's execution still burning in their minds, and President Johnson's pledge never to yield echoing in their ears, began to extract their support for the war in Vietnam.

By 1970, the war was no longer only being fought in Vietnam; it was also being fought on the mainland of America. Millions of students around the country demonstrated against a war which they felt to be unjust and inhumane. Their protests led to conflicts with local police, and even the National Guard in some instances. One such instance occurred on May 4, 1970, and resulted in the Ohio National Guard opening fire on a group of protesters at Kent State University- killing 4 and wounding 9 (Zaroulis; p.319-20). John Filo was at the scene that day, and described the aftermath as such:

"I think I took three steps and said, 'Wait a minute, someone's got to document this.' I turned back around. Wounded and dying people are laying all around me. Other people are pulling themselves up off of the ground. No one is going near the body. And then this girl, Mary Ann Vecchio,comes running up the street and kneels down beside the body. I started walking toward her. Her body was shaking... she was crying. And then she screamed- a God-awful scream. My reflexes took over, and that was it. One frame" (Leekley; p.78)

Filo's reflexes captured what is today one of the most memorable photographs of the time period. This image caused a dramatic shift in the coverage of the Vietnam War, as news agencies began to direct more of their energy toward the war at home, and less at the conflict in Vietnam. The outrage over this incident instantly reached every household in the nation thanks in part to Filo's photograph. The image of Mary Ann Vecchio's screaming face undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the minds of millions of Americans, and reminded them that the students protesting the war in Vietnam were children just like their own.

The incident at Kent State and in turn, John Filo's photograph, sparked random violence against Federal buildings housing everything from draft boards to a mathematics research center in Wisconsin (Debenedetti; p.281-2). Newspapers across the country were dominated by headlines such as "7,000 Arrested in Capital War Protest; 150 Are Hurt as Clashes Disrupt Traffic"(The New York Times; May 4, 1971; p.1), as the press began to document the events of the protest movement with a distinct emphasis on protester casualties, and government miscues. Filo's photograph turned the tide once and for all in favor of the Vietnam protest movement, as people across the country had only to be reminded of that image for inspiration in their struggle against American involvement in the Vietnam War. |

|

The nail in the coffin so to speak for the public image of the Vietnam War, came on June 8, 1972, when a South Vietnamese fighter plane swooped in on a cluster of its own soldiers, and some women and children, and opened fire (Leekley; p.88). Huynh Cong "Nick" Ut happened to be in the right place at the right time that day, and captured the group as they attempted to flee the cloud of burning napalm behind them. His photo was seen on the cover of Time later that month, and is still remembered today as one of the most infamous images of the Vietnam War.

A New York Times advertisement in 1990 testifies to the timelessness of Ut's photo. The advertisement was for a Peter Jennings special report about injustice in Cambodia entitled "From the Killing Field" (Garfinkle; p.225). Ut's photo helped push the Vietnam War into the realm of the greatest political disasters of all time. The timely photo was another example of the mindless killing going on in Vietnam, and proved once and for all that the war of attrition that the United States had been fighting was not half as precise as the government led on.

The aforementioned three photographs and their effect on the opinions of the American public during the Vietnam War are a testament to the continued power of the photograph, in spite of the newfound dominance of television as a news medium. These three photographs, and others like them, had a profound effect on the Vietnam protest movement- the ramifications of which made the Vietnam War the most infamous in our history. Perhaps the infamy of Vietnam is a direct result of one-sided, or uninformed reporting by the news media, or perhaps it is a result of the sensational photos that dominated the news of the time. Whatever the case may be, Vietnam was, like every other war- filled with death, destruction, and anguish. The thing that made the Vietnam War different from previous conflicts was that this time journalists were there to record the most heart-wrenching of those moments on film, and people everywhere were willing to immortalize them in their memories. The late 1960's and early 1970's were a period of intense transition for America as a nation, as we became more concerned with the humanistic aspects of life as a country. This change was seen in the protest movement of the Vietnam War, as the American people were no longer willing to stand by in the face of the senseless deaths of thousands of young men and women.

Notes: