|

In 1939 Salter looked back on seventeen years of experience in

the field of book design and used his own work to deduce

a typology of the book jacket. His reputation in the field

was

based largely on this specialized art form, which was also

the book’s primary marketing tool. From his first-hand

experience he distilled the distinguishing characteristics

of the seven

main jacket types in an essay entitled “Designing

Book Jackets,” The Fifth Advertising and Publishing

Production Yearbook 1939. The Reference Manual of the Graphic

Arts (N.

Y.: Colton Press, 1939): 48a-48h. The article not only

presents an overview of design principles, but also offers

useful advice

on media

and techniques to students and practitioners. Salter's

book jacket categories, which are still valid today, are paraphrased

below and illustrated with his own designs.

1.

The formal typographical or hand-lettered jacket, which includes

no design elements but lettering.

|

|

|

Carl Jefferson Weber,

Hardy of Wessex. His Life and Literary Career,

Knopf, 1940.

|

Ralph Waldo Emerson,

Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson,

Columbia University Press 1939.

|

Back to Top

2. The typographical or hand-lettered jacket that incorporates

elements of ornamental design but avoids pictorial representation.

|

|

|

|

|Cheng Tcheng,

Meine Mutter,

Berlin: Kiepenheuer, 1929.

|

A.

J. Cronin,

A Thing of Beauty,

Boston: Little, Brown, 1956

|

Franz

Carl Weiskopf,

Das Slawenlied,

Berlin: Kiepenheuer, 1931. |

Back to Top

3. The typographical, hand-lettered, or hand written jacket that

intends to suggest the action of the book. In this case pictorial

lettering evokes a mood.

|

|

|

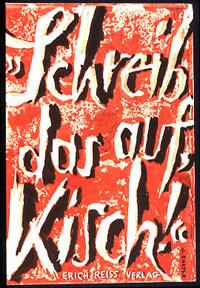

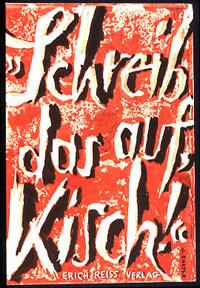

Egon

Erwin Kisch,

Schreib das auf, Kisch!,

Berlin: Erich Reiss, 1930

|

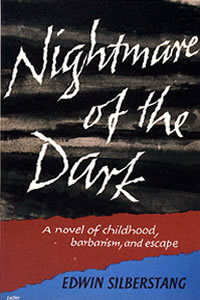

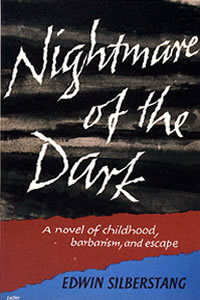

Edwin Silberstang,

Nightmare of the Dark,

N. Y.: Knopf, 1967

|

Back to Top

4.

A variation on type 3, in which ornamental

or pictorial features are added to the primary

typographical or lettered design.

|

|

|

|

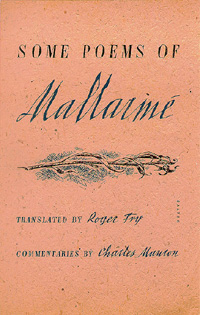

Stéphane

Mallarmé,

Poems of Mallarmé,

N. Y.: Oxford University Press, 1937.

|

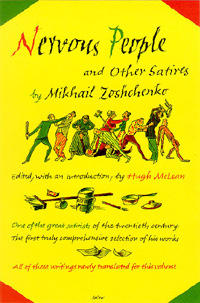

Mikhail

Zoshchenko,

Nervous People and Other Satires,

N. Y.: Pantheon, 1963.

|

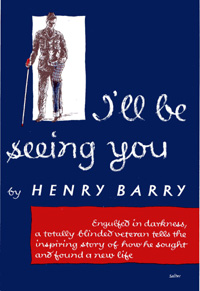

Henry

M. Barry,

I'll Be Seeing You,

N. Y.: Knopf, 1952. |

Back to Top

5.

The pictorial design suggests the atmosphere

of a book by depicting specific details of its

contents. Here the lettering

supplements or explains the imagery, which

is the artist’s

own interpretation of the contents.

|

|

|

|

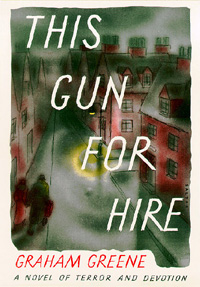

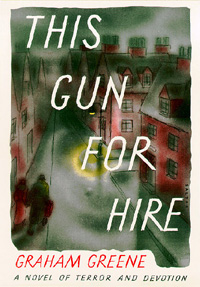

Graham

Greene,

This Gun for Hire,

Garden City: Doubleday, Doran, 1936.

|

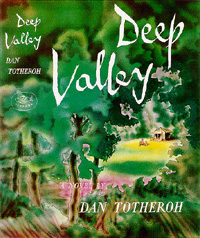

Dan

Totheroth,

Deep Valley,

N. Y.: L. B. Fischer, 1942.

|

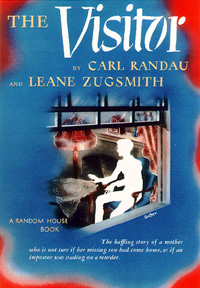

Carl

Randau and Leane Zugsmith,

The Visitor,

N. Y.: Random House, 1944. |

Back to Top

6.

The pictorial design that derives completely from the

atmosphere of the book. Although an illustrative jacket,

it does not need to draw on specific concrete or realistic

scenes. This category conveys

emotions

rather than

facts and is therefore the most suggestive and stylistically

abstract. Nonetheless, it is necessary to read the text in

order to design such a jacket.

|

|

|

|

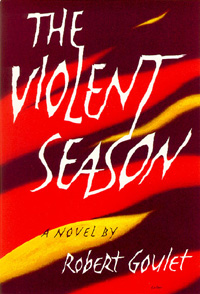

Robert

Goulet,

The Violent Season,

N. Y.: Braziller, 1962

|

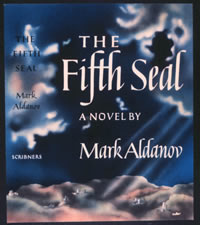

Mark

Aldanov,

The Fifth Seal,

N. Y.: Scribners, 1943.

|

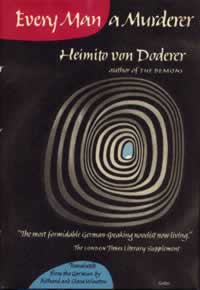

Heimito von Doderer,

Every

Man a Murderer,

N. Y.: Knopf, 1964 |

Back to Top

7.

The poster style jacket. With directness of concrete imagery,

this category relates most closely in style and intention

to commercial advertising art.

|

|

|

Leo

Matthias,

Ausflug nach Mexiko,

Berlin: Verlag Die Schmiede, 1926 (binding). |

Frank Buck & Ferrin Fraser,

Fang

and Claw,

Simon and Schuster, 1934.

|

Back to Top

|